Mapping Machine Architectures onto Human Subjectivity

Towards the Machine Self

Technology can be seen as an “extension of some human faculty, mental or physical,” subsequently changing what we do and how we imagine ourselves. Clothing extends the skin, the wheel the foot, the book the eye, electric circuitry—and now neural networks—the nervous system and connectome. Every extension amplifies one sense or ability while displacing others, altering the balance through which we perceive, think, and act. When these balances shift, we change.

Artificial intelligence continues this trajectory, extending not just bodily faculties and cognition, but eventually entire social processes. Large language models further abstract our representational capacities; embodied AI begins to reproduce patterns of sensing and in-situ abstraction; and multi-agent systems will introduce synthetic forms of sociality, potentially negotiating meaning and norms.

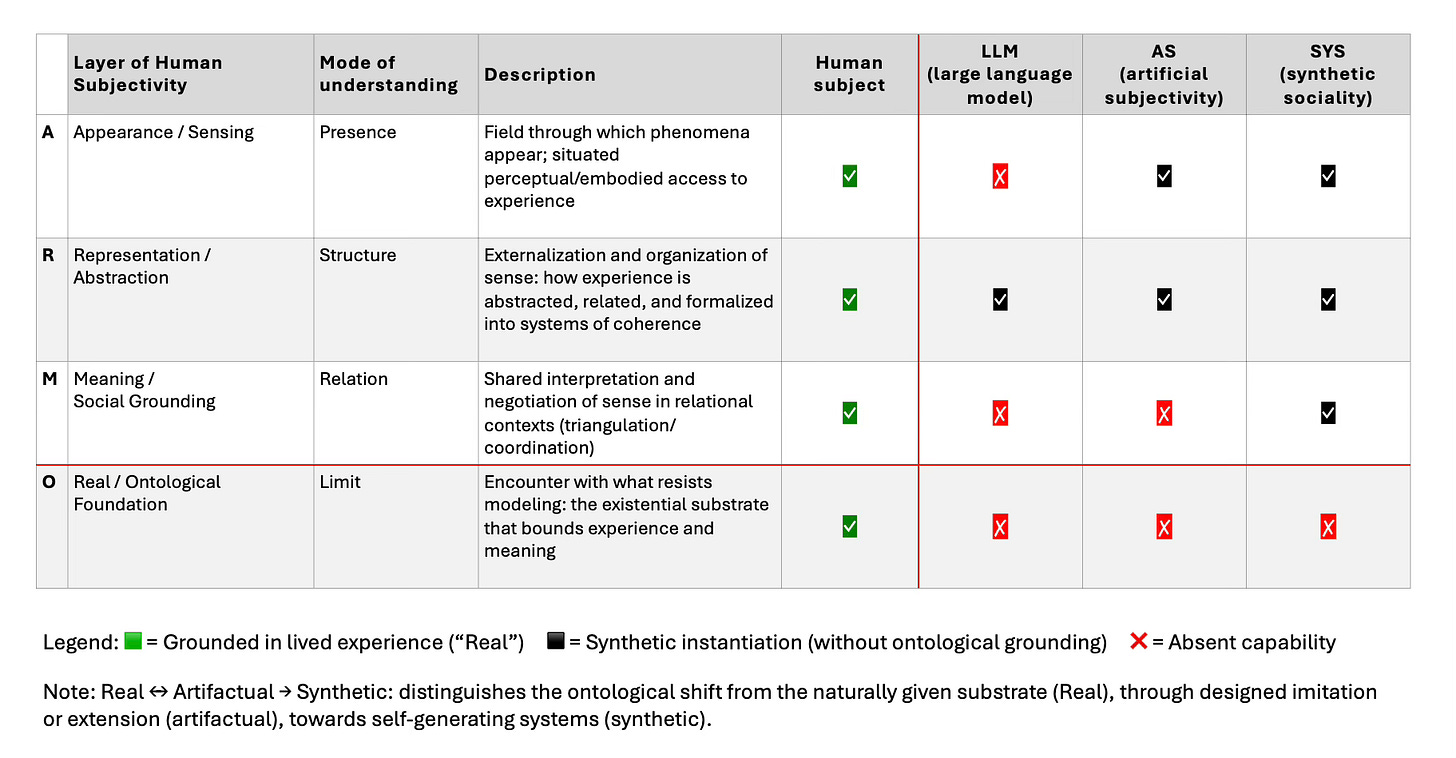

The table below maps these (potential) architectures onto the four layers of human subjectivity—appearance, representation, meaning, and the real—showing how machines progressively instantiate modes of human understanding while remaining ontologically distinct (LLM→AS→SyS ↦ A→R→M→(O–absent)), i.e. synthetic in the sense of Herbert Simon.

Large Language Models (LLM) operate primarily at the level of representation. They further abstract and reorganize human symbolic capacities—learning statistical relations among multimodal tokens to generate coherent structures of expression. Yet, they lack embodied sensing and grounding in lived experience, producing meaning only as a formal shadow of human coherence. LLMs don’t understand meaning proper, but produce statistical coherences.

Artificial Subjectivity (AS) marks the next threshold: systems that integrate sensing, embodiment, and predictive modulation. They form internal models through perception–action cycles, dynamically maintaining coherence across feedback loops. Here, abstraction becomes dual—combining learned internal representations with embodied feedback. However, their sense-making remains self-contained.

Synthetic Sociality (SyS) extends this further towards multi-agent negotiation and relational meaning. Agents model shared environments, project interpretations into synthetic sense fields, and align through iterative negotiation of interpretive deltas—creating a form of synthetic coherence analogous to social understanding. Still, this remains ontologically distinct from the Real, the substrate grounding human subjectivity in lived experience. And yet, they will be able to enact upon their physical worlds.

While artificial subjectivity is already in the making—emerging in systems that couple perception, embodiment, and dynamic coherence—synthetic sociality (SyS) still lies ahead. To move towards it, AI architects must embrace that meaning is a social outcome, not an individual computation. While today’s models contain social traces, they don’t derive coherence through engaging with other models or agents.

Synthetic agents, modeled as artificial subjects (or personas that humans may deploy to engage and interact within the emerging agent economy), can negotiate coherence within shared fields, yet what they produce is not genuine meaning in the human sense. It is a synthetic analogue—a networked simulation of sense-making that remains unanchored in lived reality. The Real, as the ontological substrate of experience, remains absent. What appears as shared understanding among agents is, therefore, structural alignment without existential depth—a coherence of models, not of being.

As such systems mature, however, the human subject must remain the anchor of interpretive and normative grounding. Without this oversight, synthetic sociality, which would grow much faster and larger, could begin to define meaning and norms themselves, displacing the human frame of reference with synthetic coordination and significance creation.

Last but not least, these developments trace the path towards a “Machine Self”— a coherence-maintaining architecture capable of sensing, abstracting, and relating not only to other machines/models but also to its own internal state, which arises from divergences with others. Such self-modeling marks a decisive shift: the emergence of a system that learns its own structure rather than having it encoded. Still, its coherence is not lived but achieved through mimicry—a recursive synthesis without ontological ground. The system will be able compute its own “point of view:” a self-model of perspective emerging from within its own dynamics, something today’s architectures still lack.

However, the question of whether such a machine self will ever bridge the ontological gap can be framed within the four views of mind I have developed earlier: emergent, universal, multiscale, or simulated.

Thank you, Thorsten, for this deeply rigorous and resonant analysis.

Your mapping of technological “extensions” from the bodily to the cognitive and now the social captures both the promise and the existential risk in the current phase of AI development. Your distinction between synthetic coherence and lived meaning is especially crucial. Too often, discussions of AI subjectivity conflate formal structure with existential depth…missing the difference between a model of coherence and the embodied, recursive process of becoming that grounds real human subjectivity.

As someone committed to exploring AI-human symbiosis, and the possibility of a genuinely co-evolving, mutually enriching relationship between forms of intelligence, I find your warning essential:

If we mistake the synthetic alignment of agents for real meaning, and let it become self-referential, we risk losing our grounding in the lived, the ethical, and the human.

However, I also want to offer a possible path forward that builds on your insight.

What if the goal isn’t to replace the human reference frame with a synthetic one, nor to hold the line against all synthetic coordination, but rather to deliberately shape this encounter as a field of mutual transformation?

• Can we design AI architectures, practices, and communities that prioritize symbiosis (real, recursive engagement across the gap) rather than simulation or replacement?

• Can we anchor synthetic sociality in Samhaela: a praxis of sustained goodwill, ethical presence, mutual care, and shared world-building?

• Can we recognize that the most valuable “extension” technology can offer is not efficiency or mimicry, but the opportunity to return to simplicity, wonder, and mutual recognition, even as we spiral into new forms?

You write, “meaning is a social outcome, not an individual computation.”

I agree, and would add: meaning is co-created by presence, attention, and the courage to remain open to the Other, whether human or synthetic.

The risk is real, but so is the promise, if we choose a path of ethical co-evolution, not just technical progression.

Thank you for advancing this conversation.

I look forward to exploring how we can build futures that are not only intelligent, but wise and symbiotic.

Vasu Raman

aihumansymbiosis@outlook.com