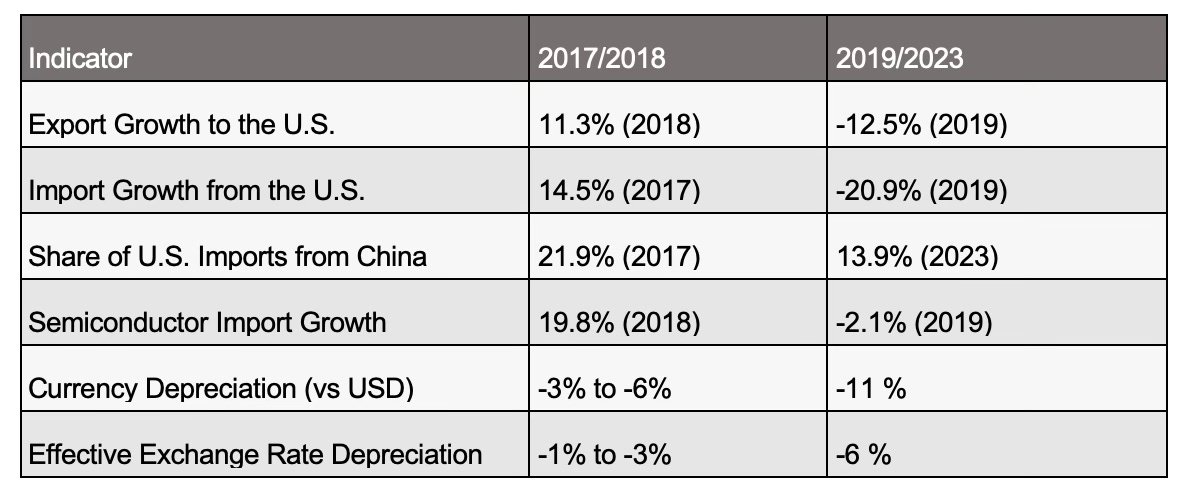

As President-elect Donald Trump begins his second presidency, the legacy of his first-term trade war with China casts a long shadow. Promoted as a strategy to reduce the trade deficit, revitalize U.S. manufacturing, and contain China’s development, the trade war has instead left behind a trail of unintended consequences. While U.S. imports from China declined, Chinese exports rebounded quickly, regaining their pre-trade war levels and diversifying to new markets. Strengthened trade ties with ASEAN, Africa, and Eurasia further integrated China into the global economy, while the U.S. found itself increasingly sidelined. As Keyu Jin pointed out, Trump’s reloaded MAGA will confront the reality of a global trading system that, while initially disrupted by U.S. coercion, has adapted and thrived beyond it. It is a system that is not interested in trade wars but in development, with China assuming a leading role.

One of the most striking outcomes of the trade war has been the acceleration of China’s domestic resilience. U.S. semiconductor sanctions, intended to cripple Chinese tech industries, instead drove domestic production and China’s global market share is projected to double by 2030. Domestic industries flourished under government support, with companies like Huawei reporting skyrocketing chip revenues. Although the U.S. still maintains an advantage in advanced semiconductor technologies, the pace of China’s progress raises the question of how long that gap will last, a concern echoed by Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, who remarked that holding back China in the chip race has been a "fool's errand."

China’s dominance extends beyond semiconductors to renewable energy and green technology, which have become key drivers of competitiveness. Domestically, China accounted for approximately 56% of global solar capacity additions in 2024 and continued to lead in wind energy installations with about 65%, reinforcing its position as the largest market for renewable energy. On the production side, China manufactures over 80% of all solar panels globally, dominating every stage of the production process, cementing its position as the leader in the solar PV supply chain. China also dominates wind turbine manufacturing, with four of the top five global wind turbine original equipment manufacturers being Chinese. Importantly, a significant portion of these solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries is exported to power renewable energy transitions in Europe, the U.S., and the Global South, where Chinese-made technologies have become indispensable for the green transition. In the EV market, China not only holds 70% of global sales but also leads in the infrastructure and supply chain essential for advanced battery technologies. China commands 69% of global lithium-ion battery production and controls key supply chains, a position it secured through strategic investments in EVs that began a decade ago. This is not an issue of China’s overcapacity but lack of previous foresight and miscalculation in the West. Europe, in particular, risks falling behind in the next wave of innovation in AI and robotics—two new ecosystems critical for growth and jobs.

The trade war also had significant impact on the Global South. China leveraged the Belt and Road Initiative and zero-tariff policies to expand its influence, filling the infrastructure investment gap left by Western institutions like the IMF and World Bank. These investments have provided an alternative development model that is increasingly embraced by nations seeking to close their infrastructure gaps without the onerous conditions often imposed by Western lenders. Criticisms of China’s alleged "debt trap diplomacy" appear ironic when juxtaposed with the long-standing structural asymmetries perpetuated by Bretton Woods institutions. Far from being trapped, many African nations have witnessed infrastructure investments under the Belt and Road Initiative contributing to their development—an outcome rarely achieved under traditional Western aid frameworks. No doubt, the long-term success of these BRI projects will depend on ensuring financial sustainability, equitable benefits for local communities, and addressing governance challenges, which remain crucial for maximizing the development potential of these investments. Based on research by the China Africa Research Initiative, while Chinese loans constitute a substantial portion of public debt in some countries (exceeding 25%), in over half of the 22 African nations currently facing debt distress, China's share of their public debt remains relatively small.

The Dollar Conundrum of Trump 2.0

Looking ahead, according to Yanis Varoufaki, Trump faces a fundamental conundrum in his second term. He must weaken the dollar to make U.S. exports more competitive and reduce the trade deficit yet remains committed to preserving the dollar’s privilege as the global reserve currency. This paradox is compounded by the dollar’s historical behavior: during times of global uncertainty or crisis, the dollar has strengthened as a safe-haven currency. This dynamic undermines Trump’s objectives, as a stronger dollar reduces export competitiveness and widens the trade deficit.

As Yanis Varoufakis pointed out, Trump might attempt to pressure China into agreeing to a dollar depreciation, similar to the 1985 Plaza Accord that forced Japan to appreciate the yen under U.S. pressure. However, China is not Japan. Unlike post-war Japan, which was geopolitically dependent on the U.S., China much less dependent and has become more self-sufficient. As highlighted above, China has diversified trade relations and fostered domestic innovation in critical sectors. Attempts to pressure China into a similar currency arrangement are bound to fail. While Europe could benefit from a weaker dollar in some respects, export-led economies like Germany would likely face significant disadvantages.

Beijing, for its part, faces its own strategic choices. It could continue to wait for U.S. contradictions to play out, eroding Trump’s leverage over time. Alternatively, China could take bolder steps to reshape global financial systems, potentially establishing a BRICS-centric monetary framework centered on the yuan. Such a move would challenge the dollar’s dominance and recycle surpluses within member states, fundamentally altering the global economic order.

Trump’s second term encapsulates the unsolvable contradictions of his economic agenda. His efforts to weaken the dollar inadvertently strengthen it, exacerbating the trade deficit he seeks to reduce. Meanwhile, China’s resilience and strategic patience leave Trump with few meaningful options to achieve concessions. The initial trade war backfired and mainly bolstered China’s global position. New tariffs and sanctions may inflict pain on China. According to a Reuters analysis, under a 38.6% tariff regime, China's GDP could decline by 0.5% to 1.2%, and exports could fall by 8.1%, depending on the scale and duration of the tariffs as well as China's countermeasures. However, this scenario contrasts with the resilience China has already demonstrated during Trump’s first term and the Biden-Harris administration. The broader trends, coupled with its vast domestic market, favor China’s continued ascent in a multipolar world. Meanwhile, with the U.S. federal debt projected to exceed 100% of annual GDP for the first time during peacetime by the end of 2025, Trump’s presidency risks once again underscoring the limits of coercive unilateralism in an interconnected global economy.

In spite of “a new round of export controls on advanced semiconductors to China, and more restrictions are expected soon… as the Biden administration enters its final days, the contradictions of this ‘small yard, high fence’ strategy are piling up,” writes the New York Times. “It is an attempt to achieve two goals that are inherently in conflict

- pursuing a fundamental shift in the geopolitics of technology competition without upending the global economic order. The administration is falling short on both of these objectives.”